Top: Arthur Jibilian (lower left corner) in front of the General Mihailovich statue on Ravna Gora in Serbia, September 2004.

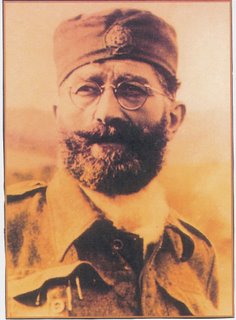

Bottom: Signed photo given to OSS Radioman Arthur Jibilian by General Mihailovich in 1944.

Note reads: “To Mr. Jibby Jibilian, ally and friend in these difficult days of the battle for freedom.’’

THE AMERICAN RADIOMAN RETURNS TO SERBIA TO PAY TRIBUTE TO GENERAL DRAZA MIHAILOVICH

“I wonder if Mihailovich knew that

we were desperately trying to help him.”

Arthur Jibilian, Halyard Mission veteran

Pranjani, Serbia, Sept. 12, 2004

He is among the last of them. The last of the living OSS veterans of the Halyard Mission. 81 years old, with vivid memories on his mind and gratitude in his heart, Arthur “Jibby” Jibilian, the ‘radioman’, made the milestone journey back to that far away place where he had been a young man in a big war. On September 12, 2004 Arthur Jibilian would once again find himself in the village of Pranjani, Serbia, a plateau 55 miles south of Belgrade, this time for the celebration of the 60th anniversary of the amazing thing that had taken place there. Two eternal marble plaques, one engraved in Serbian, one in English, were being officially dedicated, marking an event that has remained a defining moment in the lives of all those who participated. Jibby had lived to see it happen.

Of those still living who were invited for the historic commemoration, only a few managed to make the trip. Robert Wilson, 79 and Clare Musgrove were two of the airmen who made it. George Vuynovich, who had been stationed with OSS in Bari, Italy and George Knezevich, his friend, were also present. Others were not able to make it, and too many of the others did not live to see this day, among them the late Richard L. Felman.

This commemoration was a milestone in ways the radioman from Ohio, a World War II veteran whose memory continues to serve him well, could not have even conceived of. The Serbian press would report heavily about the dedication event in Pranjani, and the legacy of General Mihailovich would be brought to the forefront if only for a few days in the homeland that had turned it’s back on him, the same homeland that he had served so valiantly and loyally, despite knowing that his fate had already been decided. On this September day in 2004 Belgrade officials, American diplomats, Serbian veterans and civilians, and grateful American airmen and Halyard Mission members would give the General his day in the light.

Serbia’s Foreign Minister Vuk Draskovich and his Serbian Renewal Party made the historic visit by the Americans possible. He publicly voiced the hope that the story of the rescued airmen, the essence of the Halyard Mission, would help ‘right a historic wrong’, indicating that the Serbs want to ‘build a future Serb-American alliance on the basis of historic truth.’

Arthur Jibilian lived that truth.

Born on April 30, 1923, in Cleveland, Ohio and raised in Toledo by his cousins Sarkis (Sam) and Oksana (Agnes) Jibilian, he was 19 years old when he was drafted into the Navy on March 15, 1943. He had tried to enlist following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor two years earlier when he was only 17, but he missed one letter on the eye exam and was advised to come back at a later time. He stayed home to care for his cousin who’d been diagnosed with lung cancer. It was shortly after his cousin passed away that Fate called for him to enter the war. He began his training as a ‘Radioman’ in Boot Camp at Great Lakes.

One day Lt. Commander Green from the Office of Strategic Services (O.S.S.) arrived on the base looking for recruits. Jibby was in his sights. He remembers:

"He wanted to talk to all those who spoke a foreign language. I spoke Armenian, so I was interviewed by him. In my case, Armenian wasn’t particularly important, but he said that OSS needed radio operators desperately. Radio operators, usually in conjunction with a “team”, would parachute behind enemy lines and relay information regarding troop movements and activities. They might blow up bridges and railroad tracks and harass the Germans in any way possible. He pointed out that the mission(s) were voluntary and extremely dangerous. He was very up-front about everything. I told him that I was interested and volunteered. (After all, I was more expendable as I had no immediate family and I might, just possibly, be more valuable with OSS than if I were on a ship).

Just prior to taking my Radioman exam, I received orders from OSS to report to Washington, D.C. I was placed on “detached temporary duty” with the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). They taught me to code and decode messages, operate their three-piece radio consisting of a transmitter, receiver and power pack. It all fit into a small suitcase so that one could “mingle in a crowd” carrying it, looking like a refugee or traveler.

We then went to Ft. Benning, GA for parachute training. Normal training takes five weeks. We made it in seven days. We made three jumps there and then two more at Ft. Bragg, taking part in army maneuvers with Special Ops groups.

We were then sent overseas, via liberty ships, ending up in Cairo, Egypt, staying in one of villas occupied by President Roosevelt during the Teheran Conference.

I was informed that a Lt. Eli Popovich would be interviewing radio operators for a mission into Yugoslavia. Col. Lynn Farish and Lt. Popovich were going into Yugoslavia and needed a radio operator. Col. Farish had been in Yugo before, but had had no radio operator, being dependent on the British Missions to relay his reports. This was not acceptable to him, or to OSS. I was thrilled when Eli (we were quite informal in OSS) selected me.

We parachuted into Partisan territory, on March 15, 1944. Initially, I failed to make radio contact with the base and everyone, including me, began to doubt my competence. Finally making contact, we discovered that base had not been listening for us as the mission was scheduled to be cancelled. We were just getting comfortable, when the Germans, using a direction finder, locked in on my radio signals. When I began transmitting, German Stukas and Messerschmits strafed and dive-bombed our positions."

The Germans were relentless. Sending a contingent after the mission, they kept up the pursuit for five days and six nights. This was a week that Jibilian would never forget.

"We were in summer khakis and as we climbed the mountain trails, the air became colder and colder. We ran into snow, sometimes sinking so deep that we had to help each other lift our feet out of the drifts. When we stopped for a 10 minute break, we were soaked with sweat and the clothes literally froze to our bodies. When we started to “pocret” (march), we quickly generated enough heat to melt the ice.

We had little to eat, subsisting on goat cheese and bread with straw, given to us by the Serbian peasants. We all suffered from diarrhea."

This first mission lasted for two months. While on this mission they would learn that the Serbs were protecting a number of fallen Allied airmen who were hiding from the Germans. On their way out of Yugoslavia this first time, Jibby’s group managed to pick up about a dozen of the airmen who had been shot down while bombing the oil fields of Ploesti, Romania and brought them safely out of the country. Jibby was awarded the Silver Star for his participation in this mission and treasures the recognition to this day.

He also remembers the atmosphere that pervaded throughout the duration of the mission to Partisan territory. Not all of the tension was created by the German enemy surrounding them. This atmosphere would become especially evident in retrospect after a future mission would take the Americans into Chetnik territory.

It wasn’t long after Jibby’s first wartime ordeal that Colonel Kraigher of the 15th Air Force contacted OSS to let them know that he’d gotten word that 50 American airmen were stranded in the Serbian village of Pranjani, Yugoslavia. Thus, another mission was activated. This time it would be sent into Chetnik territory. The mission, named Halyard, would be composed of Captain George “Guv” Musulin, Lt. Mike Rajacic and Navy Radio Operator Arthur “Jibby’ Jibilian. All they knew was that General Draza Mihailovich, leader of the Chetniks, had kept these airmen safe while they waited to be rescued. They had been shot down while bombing the oil fields of Ploesti, a extremely valuable resource the Nazis were depending on, and the Germans were intent on capturing them. After falling into Chetniks hands, the airmen had been fed and protected and were now just waiting. All the while, however, the Germans continued their search and were out for the blood of those who were protecting them. Those in charge estimated that the mission established to rescue the Americans who had fallen behind enemy lines would take a short seven to ten days. How wrong they were.

Political concerns came into play. It must be remembered that this was all taking place after the Allies had made the unfortunate decision to abandon Mihailovich in favor of Tito. False charges of collaboration with the Germans were leveled against Mihailovich to justify the tragically misguided abandonment of their most loyal ally. Thus, establishing a mission to rescue the American airmen now being kept safe in Chetnik territory under Mihailovich’s command created a real dilemma for those in charge. The irony was not lost on the young Americans who had volunteered to parachute in and evacuate the airmen.

"If we went in and rescued the Airmen, says Jibilian, how could Mihailovich be called a collaborator? The British were vehemently opposed to anyone going into Chetnik territory on any pretext, as were the Russians.

As a result of these “political concerns” our mission was delayed and/or aborted a dozen times. We were to jump on July 3, but it was not until August 2, 1944, that we finally jumped into Pranjani.

Two things made the mission finally successful:

Musulin asked for an American pilot, an American plane and an American jumpmaster, the morning of August 2. We were in Yugo that night.

We were told that Gen. Bill Donovan, head of OSS, and President Roosevelt were discussing the situation. The president mentioned that the British were unhappy with the proposed mission. Gen. Donovan is alleged to have replied: “Screw the British, let’s get our boys out”.

The group would find not just 50 Americans when they landed in Serbia, but 250, and Jibby remembers the condition he found them in:

Many were in bad shape, having been wounded by flack and/or sustaining injuries upon landing or while attempting to evade capture by the Germans. I cannot say enough about the care and protection that our wounded received from the Chetniks and the Serbian people. They risked their lives to shelter and protect our boys. The peasants fed the wounded when they, themselves, had nothing to eat. You must remember that the land had been ravaged by the Germans and the Civil War further depleted the resources of the farmers, giving meaning to the phrase “they were dirt poor.”

Because there were so many airmen, the decision was made to evacuate them during daylight. A German garrison stood only 20 miles away. When a suitable stretch of ground was found in the area to fashion a landing strip, Americans, Chetniks, and farmers all worked together to make it happen.

One week later, on August 10, 1944, the first evacuation was successfully completed, without a single American casualty.

It was far from over, however. Jibby would quickly learn just what kind of ally General Mihailovich was.

"Gen. Mihailovich informed us that there were many more American airmen throughout his territory and he would funnel them to us, if we so desired. We received permission to stay and, what started out as a l0 day mission, lasted almost six months, during which we evacuated 513 Shot down American airmen, and “several” British, French and Italians."

The Ranger Mission would follow and then finally, on December 29, 1944, with Captain Nick Lalich and Jibby having remained as the sole mission in Mihailovich territory, the evacuations came to an end. The Radioman was going home.

"After a quick physical, a long, hot shower, I collapsed into a bed. The next morning, I had eight eggs, probably a pound of bacon, six slices of toast, butter, and jam, and I can’t remember how many cups of coffee. Food never tasted so good! However, my elation was tempered with the thought of the poor Serbs who had sacrificed (and were still sacrificing) for the Americans."

Reflecting back, Jibby would be struck by the difference he had discovered between his two stays in Yugoslavia.

"Having spent two months with the forces of Marshal Tito, and six months with Mihailovich, the contrast was amazing. The Partisans shadowed us, never leaving us alone with the villagers. They were always tense, and villagers were ill at ease in their presence. Once, when we were alone with a family, we were asked: “Why are the Allies backing Tito?” I had been told to simply say: “Only God knows”. Being deeply religious, they accepted our answer."

In contrast, villagers [in Mihailovich’s territory] flocked out happily, strewing flowers in Mihailovich’s path and singing and celebrating his return. All available food was scrounged so that a virtual feast could be prepared. The villagers donned their native costumes and danced and sang in Mihailovich’s honor. It was obvious that they literally adored him."

**********

Jibby would be discharged from the Navy in September of 1945 and became employed with the Veterans Administration in Washington, D.C. One morning he would read a small article in the Washington Post that would leave him stunned and shaken. The headline read: ‘Tito’s Forces Capture Mihailovich.’

At that moment, Arthur Jibilian felt compelled to do whatever he could to stop the inevitable from happening.

"Knowing that Mihailovich felt abandoned by the Allies, I decided to tell the story of the Halyard Mission to the Washington Post. I saw the editor and told him my story and how Mihailovich had saved 513 American airmen.

I did not know it, but the rescued airmen had kept in touch with one another. The met at Ft. Stephens in Chicago and sent a 20 man delegation to Washington. They contacted me and we organized a “Mission to Save Mihailovich” campaign. We distributed pamphlets, contacted the State Department, our senators, and representatives. We asked for only three things:

1. Let the rescued airmen testify at his trial.

2. Allow OSS personnel to testify at his trial.

3. Move the trial to a neutral country so Mihailovich would get a fair trial.

Even though we knew Mihailovich was doomed, we felt that if we could at least see him and let him know that we hadn’t forgot him, he would die more peacefully.

Tito’s reply: “This is an internal matter and will be handled by us”.

We tried valiantly, but Washington is a town full of very powerful lobbyists and our efforts paled in comparison with the money and influence they had.

Mihailovich was tried and executed as a collaborator. In his last speech, he concluded by saying:

'The truth is for everyone.' ”

**********

Serbia came a little bit closer to the truth this fine September day in 2004, and an American radioman discovered that nothing would ever betray the memories of a people and nation that had been part of his great journey through life. The people had not changed. He found them as he had left them.

"To say that it was a great, marvelous, wonderful, the trip of a lifetime would still not do justice to the privilege of going back to Serbia. It was a dream come true.

As usual, the Serbs treated us as though we were king and queen. We were given a young lady, Jelena Predojovic, and a young man, IIia Jatrayav, who saw to it that our every need was taken care of. We cannot speak too highly of their care and consideration during our stay.

We were interviewed by the press, filmed for TV, and interviewed by the radio stations.

As I told one reporter: "The Serbs owe us nothing. We Americans risk our lives everyday for our fellow Americans. I am in awe, however, of the Serbs and the way they took care of our shot down airmen! They fed them, sheltered them, depriving themselves of VERY scarce food. To top it off, they gave their lives rather than reveal where the Americans were hidden!!!!

I SALUTE THEM, AND I THANK THEM."

Although Richard Felman and Arthur Jibilian have spoken about how much they owe to the Serbs, they have more than paid back their debt of gratitude. I was honored to have had the privilege to call Major Felman my friend and am honored to have been given the privilege to tell the story of the American radioman who’s participation in the missions of a lifetime saved lives. Jibby, the Radioman, we salute You.

Aleksandra Rebic

November 2004